MERIAN THE PIONEER NATURALIST

MERIAN THE PIONEER NATURALIST

Restoring the German scientific pioneer to her rightful standing

Published: 21 August 2018

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

A completely extraordinary woman, pioneering German/Dutch naturalist and artist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) is celebrated in a delightful new book by Getty Publications, the publishing arm of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian by Jacob Marrel, 1679

Co-authorship by classical scholar Sarah B. Pomeroy and Oxford entomologist Jeyaraney Kathirithamby unlocks special techniques to learn about ‘forgotten women’ while never losing sight of Merian’s achievements as an artist and naturalist.

Over lunch, Jeyaraney, an entomologist in Oxford’s Department of Zoology and St Hugh’s College, explains that the book is part of a sustained and overdue re-assessment of an altogether incredible individual.

True, Merian was featured on the German 500DM banknote before it was swallowed up by the Euro. And her timeless vellum plates of insects and flowers were hoovered up by Russian Tsar St Peter the Great, at the point of her death.

But that’s not to say that she’s a household name, nor that she wasn’t almost completely forgotten after the mid-eighteenth century despite laying several important foundations towards the classification and taxonomy of the natural world. She was an apparently fearless individual, explorer, scientist and artist.

Born in Frankfurt and later resident in Amsterdam, Merian collected silk worms as a 13-year old and dedicated herself to solving the mysteries of metamorphosis through intricate and sustained observation of nature. This she would achieve.

Marriage, two daughters and then separation and later divorce, the latter rare in the 17th Century, resulted in life in an uber-strict Calvinist settlement, one can guess partly from necessity. Her youngest daughter Dorothea just 7, she was 38. Fourteen years later, improbably and at the age of 52, Merian jumped on a ship and went off to the then-Dutch colony Surinam, a tropical sugar plantation on the north-east coast of Latin America, today Suriname.

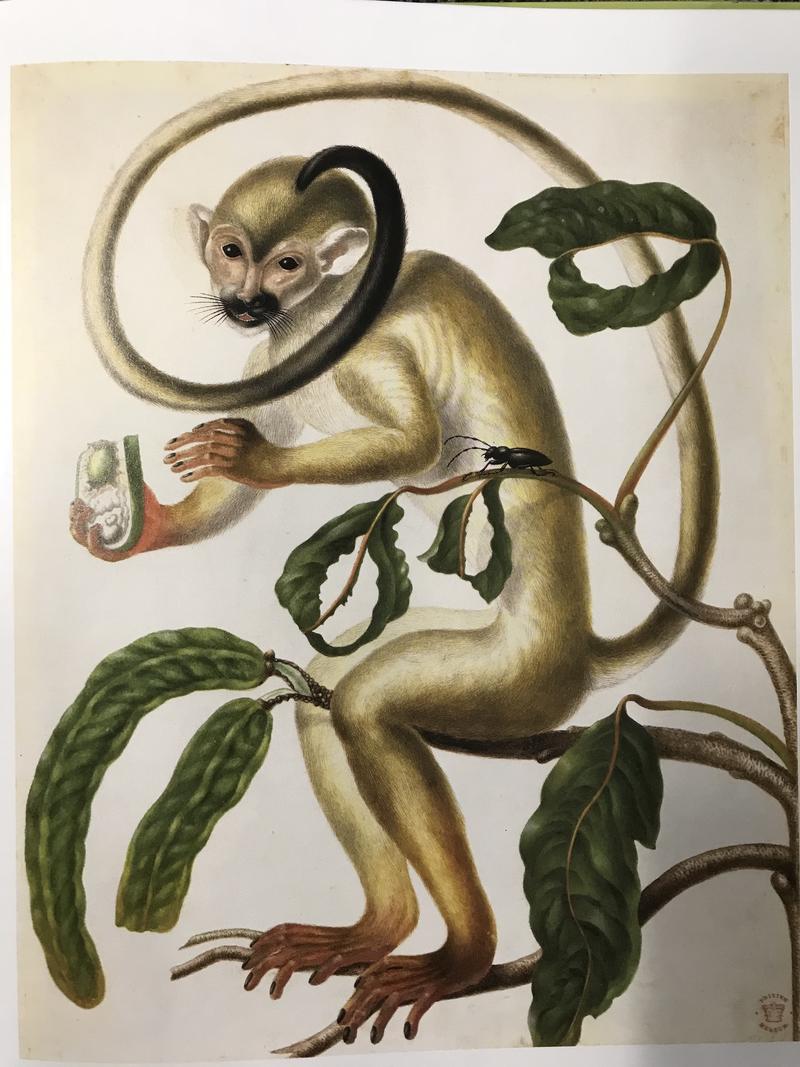

Shimbillo Tree with Squirrel Monkey, 1701-5

Learning painting as a child from her stepfather in Frankfurt, surreptitiously and with watercolours and gouache owing to a (male) Guild monopoly on oils, Merian possessed a searing talent as an artist. She was also an intelligent woman of business.

But her talent was allied to an equally vigorous desire to see behind surfaces and penetrate the mysteries of natural processes, in particular than apparent miracle whereby an egg becomes a caterpillar, and hence a butterfly. The prevailing wisdom was that butterflies were spontaneously generated from the mud. This became her life’s work, with successive publications The New Book of Flowers; The Caterpillar Book, and The Insects of Surinam building an outstanding early modern record of specimens, wrought with such precision that the aesthetic is powerful partly for being unself-conscious.

This is also where it gets interesting, because while recently experts have begun to pick apart which of the paintings were by her daughters Johanna and Dorothea, neither, despite great talent, possessed their mother’s almost fanatical will for showing the entropic face of nature, the browning leaves curling or rotting on the stalk, the defects; the downslope.

In this, which is not distinct from her time at the other-worldly Labadist colony in rural Friesland, Merian takes her rightful place in a distinct German aesthetic that canters from Albrecht Dürer to Otto Dix and a post-World War One sachlichkeit provocation, ‘ugliness as beauty’ and limbless victims of war trapped in egg tempera like specimens.

A watercolour of a branch of Genipapo with Sabertooth Longhorn Beetle (not seen), South American Palm Weevil (seen on right) and Euglossine Bee (partly). To the left is a Flannel Moth Caterpillar.

One of the delightful aspects of the book is that it is entirely accessible to a broad audience, and in fact Sarah B. Pomeroy, Distinguished Professor of Classics and History, Emerita, at Hunter College, dedicates the book to her grand children, and Kathirithamby to her great nephew. There are classroom resources inside the book and around it on the Getty Publishing website, suggesting a broadly and imaginative remit.

Distinguished not only by its glorious illustrations, taken from a second edition of Merian’s masterpiece The Insects of Surinam, (drawn from the Getty Research Institute) there are numerous entry points, cut-away reflections on how we recover largely missing information about the lives of women, and a user-friendly glossary.

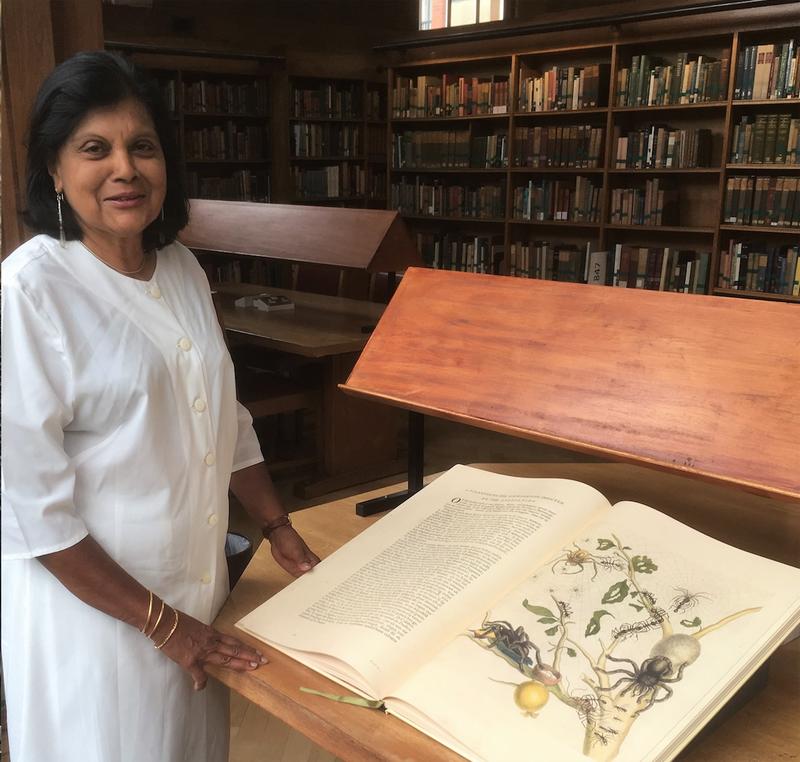

Jeyaraney Kathirithamby with Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, donated to St Hughs library by Clare and Alan Todd

Credit: Benjamin Jones

While the Bodleian LIbrary has a fascinating collection of Merian literature and engravings, Kathirithamby's college, St Hugh's, now also has a recently published copy of Merian's Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, donated to the college library by Clare and Alan Todd.

Everyone has heard of Charles Darwin and even the name of his ship, Beagle. There is a powerful society to guard the reputation of Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-78), credited with formalising binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms. But the name of Merian’s ship to Surinam is lost and her lifetime’s agglomeration of taxonomic artistic records, the foundation upon which Linnaeus built; even the idea that you booted off to a far-flung colony to study the natural world rather than make your fortune flogging slaves, all this was Merian’s too. Yet she’s comparatively unknown.

Merian was one of the first naturalists to observe insects directly, and she was the first European woman to independently go on a scientific expedition in South America. While we might today describe her as a scientific illustrator, going on to note the inherent confusion between art and science, she was nonetheless both at once, and were she a man we would have called her a great early figure of the Enlightenment. No such luck: but this book is a major contribution and also a thing of beauty, and Merian also features in a Bodleian Library exhibition that runs until February 1919. She would have approved.

Sappho to Suffrage, women who dared, free exhibition at the Bodleian Weston Library, runs until February 3rd, 2019. The Bodleian Library has an extensive collection of Merian publications and documents.

Maria Sibylla Merian, artist, scientist, adventurer, by Sarah B. Pomeroy and Jeyaraney Kathirithamby, (2018); £16.95 from Yale University Press, for UK-based alumni.

$21.95 from Getty for North American alumni.