THE STRANGE RISE OF ILLIBERALISM

THE STRANGE RISE OF ILLIBERALISM

The 2023 Pharos lecture by John Gray put Liberalism under the spotlight

Published: 14 November 2023

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

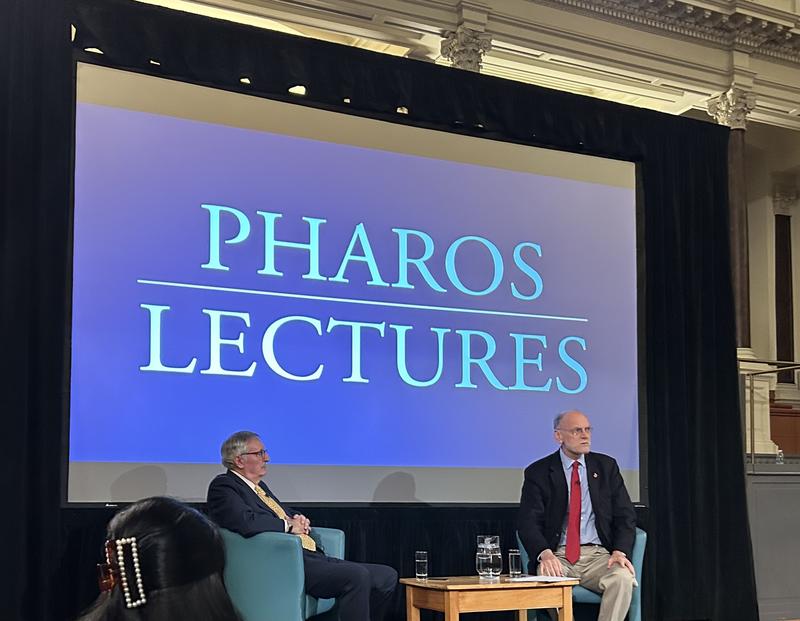

At the end of extensive discussion in the Sheldonian following this year’s Pharos Lecture given by former Oxford professor John Gray (Exeter, 1968 - pictured right), he asked an open question: how many mass demonstrations have there been in Western capitals to protest on behalf of the persecuted, mostly Muslim Uighur people in China, or the persecuted, Muslim Chechens in Russia. Apparently none, or none that were anywhere near the scale of current protests in support of Palestine.

Chechnya, he reminded the audience, was subjected to two brutal wars of repression two decades ago and their capital Grozny almost totally obliterated by Russian forces sent in by current Russian leader Vladimir Putin, along with a string of massacres and other war crimes. The majority of people would be hard put even to remember that this happened.

Professor Gray asked the question, not to necessarily deny the authenticity of some of the current demonstrations but to suggest that they show the West having an angry dialogue with itself.

It was an interesting coda to a lecture titled 'What is Living and What is Dead in Liberalism?', which had begun on the same note, with Gray pointing out that Liberalism had extensively decayed from within over the past four decades, rather than because of external attack.

This complex historical process might be filed under the heading ‘very large unintended consequences.’ The largest of them was that ‘unfettered market forces demean the common good.’

As such there was also a rueful personal note to the lecture, with Gray recalling boiling kettle after kettle of water to fill a bath to ‘an inch or two’ when there was no coal and Britain was strangled by strikes in the 1970s. His interlocutor, Professor Nigel Biggar, until last year Oxford’s Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology, also recalled reading by candle light in the 1970s as a student. Britain was bailed out by the IMF in 1976 and widely perceived to be in a bit of a mess.

‘Something had to change’. Gray explained that he was himself radicalised in the mid-1970s by these perceived failures, but went from being on the left to supporting Margaret Thatcher and her market reforms that represented the triumph, ultimately, of market forces over unions, between her initial election in 1979 ‘until the late 1980s.’

Some of this ideology she attributed to economist Friedrich Hayek, except, as Gray pointed out, he did not consider himself a conservative. Conservatism has traditionally been about conserving what is considered to be important, whereas Thatcher’s market reforms over time totally destroyed the very world she believed she was restoring, the world of her own upbringing in the 1950s that she publicly remembered and revered on so many occasions, and beyond it further memories of the Victorian age.

So yes, centralised planning had led to waste, poverty and corruption whether in Britain or in the Soviet Union, the latter destined to fail just two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But the replacement of classical liberal values with unbridled free markets since then has replaced moral values with morally vacuous consumer choice, and ultimately laid the basis for the angry populist resentment of the past decade, which would include to a degree both the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the election to the US presidency of Donald Trump in 2016 and 2017 respectively.

During this past decade the very categories of ‘left’ and ‘right’ have all but melted. Contrary to expectation the real challenge to unfettered market forces came from the radical right.

Gray made plain that in many regards his attitudes remain classical liberal ones, and to revive Liberalism would mean reviving a respect for tolerance, originally the outcome of relentless religious wars in the early modern period; to revive judgement that would actually carry moral content rather than mere technical expertise, and finally to resurrect the idea of truth as lying ultimately outside the purview of humans and thus resulting in a healthy skepticism, and humility at the personal level.

Gray joked that he may have spent too much of his illustrious career as a preeminent intellectual and thinker studying John Stuart Mill, but in the lecture he was able to pinpoint the tension in Mill that saw the great potential for humans when unshackled from religious dogma – humans essentially replacing God – while seeing that if humans perfected knowledge there would be no room left for disagreement, a notion of progress that he took from French thinker Auguste Comte and which would later prove disastrous in the hands of fascists and other illiberal western ideologies.

The current situation is one in which rights have replaced values, becoming divisive in the process. ‘Rights are useful,’ he argued, ‘but they are not self-validating moral facts.’ Gray cited the intractability of conflicting rights such as in the abortion debate in the US.

The same process has led to court battles and then the capture of the judiciary by politicians, and then a breakdown in the law that was glimpsed with the Trump-endorsed march on the Capitol.

In his just-published book The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism, which offers a new reading of Thomas Hobbes for the world of 2023, Gray notes how the most repressive regimes on earth have taken some of their lessons from the European Enlightenment, including Xi’s China which is partly inspired by the German thinker Carl Schmidt, whose ideas helped to legitimise Hitler in 1933.

‘If the state and the people are one and the same, minorities such as the Tibetans and the Uighurs can be suppressed, or obliterated, in the name of public safety.’

But with no moral vision left, Western liberals now default to the most radical group in the room and calls it ‘progress’, with the extremes of ‘woke’ amounting to ‘secular Christianity shorn of any sense of mystery,’ and in far too many cases an intolerance of different points of view that is far away from the liberalism that is supposedly on offer.

Vicious 'cancel culture', illiberal campus politics and extensive self-censorship and other forms of thought policing are among the outcomes.

Concerning global affairs, John noted that Western attempts since the end of the Cold War to export itself to Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria have simply failed.

They now have their time cut out merely to defend their own borders from hostile forces, a scenario not indistinct from the perilous situation Ukraine finds itself in, with Western support in question.

We are back to the ‘normal’ long run of human history, suggested John, defined by ‘folly and madness with occasional interludes of peace and civilization.’

The 2023 Pharos Lecture was given by Professor John Gray in the Sheldonian Theatre on 8 November, entitled, 'What is Living and What is Dead in Liberalism?' Previous lectures were given by Richard Dawkins and Jonathan Sumption. The Pharos lecture series is independent of the University of Oxford. The full lecture is available on YouTube.

John Gray is a world-renowned philosopher, political theorist and intellectual historian. He has an asteroid named after him and until 2008 he was School Professor of European Thought at the LSE. He now writes principally for the New Statesman and has authored over twenty books including the bestselling Seven Types of Atheism, Straw Dogs, Black Mass, The Soul of the Marionette, The Silence of Animals and Feline Philosophy. His latest book, recently published by Penguin in September 2023, is The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism.

Lead image: Professor John Gray (L) speaks to Professor Nigel Biggar (R) in the discussion that followed the 2023 Pharos Lecture. (Credit: University of Oxford/Richard Lofthouse). Portrait of John Gray, (Credit: Justine Stoddart).