RACE AND THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN THE UK

RACE AND THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN THE UK

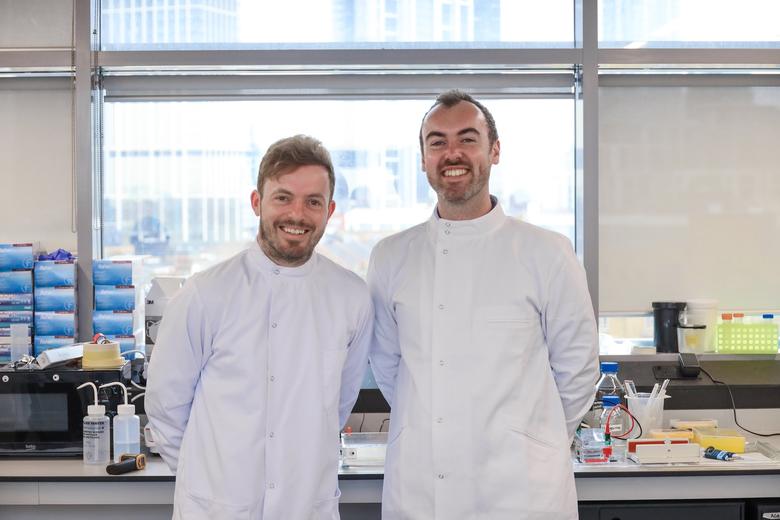

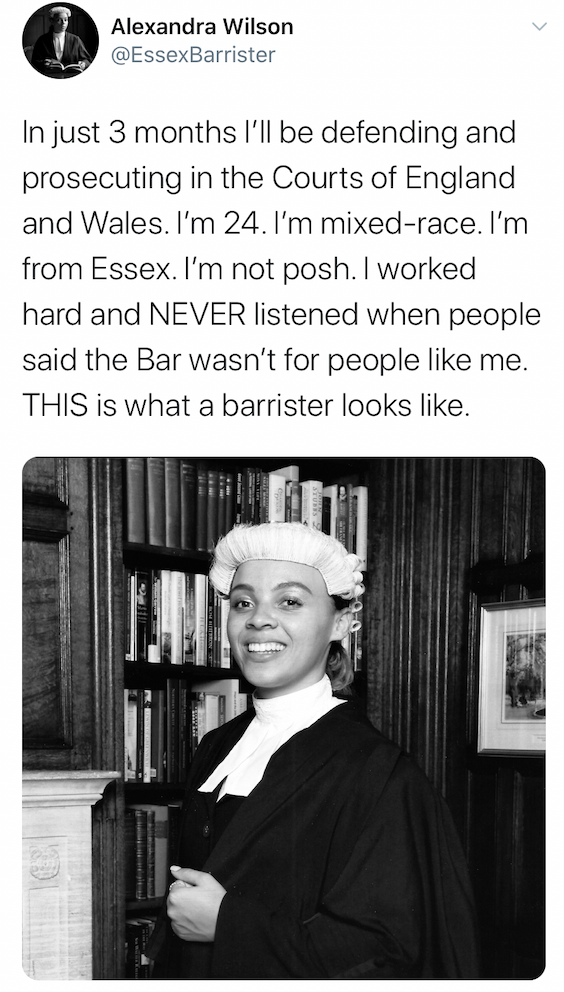

Alumna Alexandra Wilson (Univ, 2013) shares her experiences at the Bar

Published: 13 August 2020

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

Alexandra Wilson (Univ, 2013) will in October celebrate her first anniversary as a barrister following a successful first-time pupillage in 2018-19, a remarkable achievement for someone aged just 25.

She has also - miraculously so given the working hours of a junior barrister - written a book telling her story, publishing In Black and White on August 13th.

The eldest of four, raised in Woodford, where East London meets Essex, her paternal grandparents were part of the Windrush generation, who came to the UK from Jamaica in the 1950s.

As she says in the book, ‘I’m a woman. I am mixed-race. I grew up in East London and Essex. I am not posh but I’m not going to let anyone tell me that the Bar isn’t for ‘people like me.’’

The day we talk, by phone of course owing to COVID, it’s less than 24 hours since Joe Biden had declared a black woman Kamala Harris his running mate in the US Presidential elections; and just four days since Labour MP Dawn Butler, a black woman, was stopped and searched in the London Borough of Hackney, subsequently branding the Metropolitan Police racist.

The sub-title of the book speaks for itself, A Young Barrister’s Story of Race and Class in a Broken Justice System. There seems to be no better timing for this book than the sweltering hot summer of 2020.

Yet that sub-title is more capacious than it first appears. ‘Race and Class’ is a simply huge subject but if nothing else the litany of real-world legal cases that are re-told in the book point directly at intersectionality, in particular poverty and deprivation on one hand and race on the other.

When later in our conversation we turn to the controversial practice of Stop and Search in London, where Police will stop and search an individual ostensibly to reduce crime, Alex notes that the research simply doesn’t support the practice for its avowed aim, but descends all too often into ‘harrassing black people,’ who are statistically stopped far more often than whites – 38 per 1000 instead of 4 per thousand.

But defenders of the Police say that more crime is committed by black people, so it’s fair. This difficult subject is covered in the book. Three quarters of London boroughs with the highest level of violent crime are also among the top ten most deprived. Black people are more likely than any other racial group to live in the most deprived areas. 23% of children in care in 2018 were from minority ethnic groups, despite comprising only 14% of the UK population.

Alex says that ultimately addressing deprivation is the route to reduced crime, not longer sentences, and you can double or treble that where youth offenders are concerned, many of whom have been in care or have other desperate stories to tell that would explain why they were trying to sell drugs or steal chicken fillets from the local supermarket.

And that is one of the great unforced themes of the book. Time and again, in her year of pupillage, Alex is left hanging with minutes to go before being called into court, her client having not shown up at all.

As the reader, you’re left exasperated. How can the system be so inefficient? How can people be so careless about something so important? How is the young man who is handed a twelve-month driving ban able to drive away from the court having offered his speechless barrister a ‘lift to the station?’

Alex says, ‘There are a lot of things that are not up to scratch. Frankly, things fall short. There is insufficient resource.’ She says that sometimes as many as half of the defendants for lower order crimes heard only at a magistrate’s court, fail to show up during her working week (the technical term is ‘failure to surrender.’)

‘Yet I came to understand pretty fast that there are real reasons why the court might not be the top priority for an individual,’ she says. Sometimes they have been arrested for something else and are in a Police cell. More often they are living chaotic lives and get their timings wrong. Often totally overlooked is the cost of travel – they might not have a £50 train fare in their back pocket.

Despite all these shortcomings Alex loves the law and has clearly made hundreds of critical, positive differences to hundreds of deprived individuals, at the very human level of being able to represent them in ways that they relate to and understand.

This is one of the great strengths of the book, the ability to hold fast together a reluctance to be branded by the system that is in some respects broken, yet to celebrate changing it from within.

On one occasion she is wearing her wig and is berated in the corridor of a court by an agitated young Asian male who hopes she’ll go to prison herself, shouting ‘you lot have no idea…’

Yet in the very next case she makes a difference by working tirelessly with a solicitor to secure a better outcome for a young man who might have otherwise have re-offended. She notes, ‘my personal experiences meant that I could relate more to some clients than others could.’

The flipside is a string of frankly embarrassing stories from within the legal profession. They start with Alex being repeatedly mistaken for the defendant by the court usher, presumably on account of her skin colour given the absence of any other plausible reason.

But they include some extremely unsavoury comments from older, privately-educated white male barristers who obviously resent the presence of a black, female barrister. In other words the profession itself remains racist, to some degree.

Haunting the narrative is the devastating loss of a young friend Ayo, stabbed to death in London for being in the wrong place at the wrong moment, with no gang association whatsoever. He was just 17. The case set Alex on the path to a legal career – ‘I was trying to find an explanation as to what had happened…’

But much later in the book comes another bombshell, the violent and baseless detention by UK police of her aunt and uncle when she was growing up, a matter so egregious that it went through the courts, the judgement going entirely against the police.

Asked what single reform she would most like to see of the legal system in the UK, Alex says that she would like defendant names to remain unstated before conviction, owing to often lurid media coverage which stigmatizes the individual no matter what the outcome is, undermining the presumption of innocence which is such a key trait of the English justice system.

To encourage more women and minority barristers, she points directly to financial support around the critical pupillage stage, not forgetting the huge amount of unpaid mini-pupillages undertaken (‘work experience’) and that many more students have to first undertake the one year legal conversion degree course. The fees for all this cost at least £30,000 before living expenses and laptops, and sit atop the undergraduate degree that precedes it all.

Looking back on Oxford, Alex is glowing about the Target Oxbridge scheme that helped her with a mock interview following an unhelpful attitude from certain teachers at her school, who actually tried to steer her away from applying to Oxford. She also says that the teaching she received at Oxford was wonderful; less so some alarming and unpleasant racism she encountered from other students, and the awkwardness of being the only black student in her entire year at Univ.

‘I cried with joy when I heard that Baroness Amos is coming to head Univ….’ The first black, female head of house at Oxford has begun as Master of the College in August, succeeding Sir Ivor Crewe.

Although Alex studied PPE her attendance at Univ was strangely fitting because the first black barrister in the UK, Christian Cole, also attended Univ, was admitted to Inner Temple in 1879 and called to the Bar in 1883.

While reform in the legal profession has been painfully slow, (it took more than a century for the first black to be made a Queen’s Counsel, Dr John Roberts QC, in 1988), Alex believes that change is possible and that she embodies it.

Pictures courtesy of (and copyright) Alexandra Wilson. Credit for formal portrait of Alexandra: Laurie Lewis.

In Black and White, A Young Barrister’s Story of Race and Class in a Broken Justice System was published on August 13, 2020, by Endeavour.

Alexandra Wilson matriculated to University College in 2013, and after two prestigious scholarships and a degree in PPE went on to her Graduate Diploma in Law and Master of Laws. Alexandra was awarded the first Queen’s scholarship by the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, conferred on students showing exceptional promise. Alongside her paid family and criminal law work, Alexandra provides legal representation for disenfranchised minorities and others on a pro-bono basis. She is a tenant of the Chamber 5SAH, a specialist multi-practice set of barristers in central London.