CORPUS AND THE GREAT WAR

CORPUS AND THE GREAT WAR

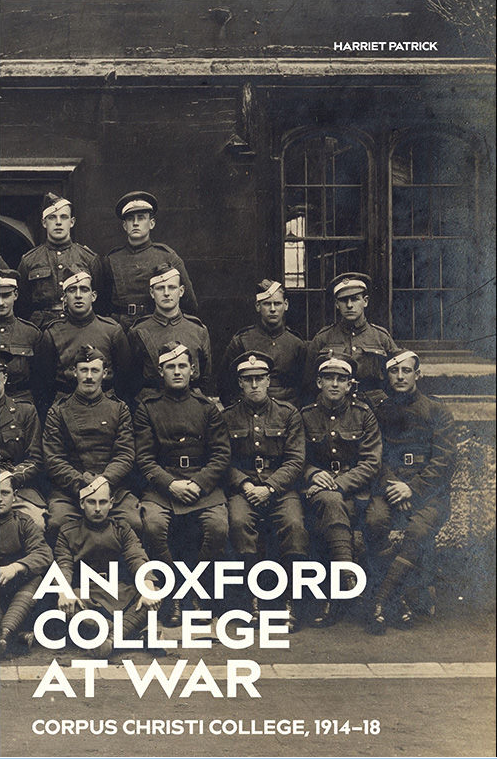

Harriet Patrick, Assistant Archivist at Corpus, has published An Oxford College at War, Corpus Christi College, 1914-18 (Profile Editions, 2018)

Published: 19 December 2018

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

Harriet has divided the book into four sections: ‘Corpus’s President and Fellows in Wartime’; ‘Corpus at the Front’; ‘Corpus Servants in Wartime’ and ‘Corpus Life and Buildings in Wartime.’ In an Afterword we get a generous, extended sense of what happened after the Armistice in November 1918, right up to the endlessly deferred Quatercentenary of the College, only finally celebrated on October 5th, 1920 and then within a Gaudy – evidence on its own of the shattering effect of the conflict on college life.

Credit: Harriet Patrick

For this reviewer, one of the book’s major contributions is to establish with greater accuracy what portion of the student body was killed. In previous research contained within the 20th Century volume of the history of the University edited by Corpus’ Brian Harrison, Jay Winter displayed a chart showing that Corpus lost 25.43 per cent of its student body, or 89 men out of 350 who signed up to active service. At the other end of the spectrum, Jesus College lost 14.48 per cent, (64/442). The historical question presented itself: why the disparity?

Harriet picks up where Jay left off, with The Oxford University Roll of Service (1920). Both authors acknowledge that this otherwise invaluable record of University members who served in the war has errors and omissions (hardly surprising), but it has taken until now to attain further clarity in respect of Corpus.

Harriet finds that Corpus’ actual fatality rate was 23.82 per cent, or 91 deaths out of 382 on active service. She then shares the stories of two Corpuscles inadvertently omitted from the war memorial in the Chapel, William Percival Griffiths (CCC Scholar-elect 1914) and John Henry Reynard Salter (CCC Commoner-elect 1917).

Neither man came up to College and matriculated conventionally, which throws up the conundrum of who to include and not include in the statistics. But for the purpose of any history of Corpus and the war, Harriet takes the approach that it would be an omission not to narrate their experience. After all, they earned their place and entered into correspondence with the college about deferring scholarships.

Griffiths obtained a commission in the 10th Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, soon promoted to lieutenant and then to Captain in January 1916; then killed in action on March 30th, 1916, aged 20. Salter, formerly a boarder at Wellington College and a great rugby player, became a 2nd lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps, missing, killed in action, on October 13th, 1917. He was just 18 years old.

Both these previously unknown biographies contribute to the wider picture of Oxford’s higher than average death rate compared to the rest of the nation, approximately 20 per cent compared to the national figure of 12 per cent. This is so because both men enlisted immediately upon the outbreak of war.

The context is useful. Oxford was a garrison town. The University had an extensive imperial connection and ethic of service. The vast weight of respectable opinion, Town and Gown, was behind the war and everyone scrambled to get into uniform in August 1914, the fellowship and servants as well as students.

Garrison town: Cadets marching along the Broad, led by a band

Credit: Bodleian Library (public domain)

This basic fact of the patriotic ethos of Oxford upon the outbreak of the war has been underestimated. The Oxford Officer Training Corps, set up after the Boer War and developed out of the Oxford Volunteer Corps, meant that August 1914, while a great shock of change in one sense, was also not unanticipated. Vice-Chancellor Thomas Banks Strong immediately set up an ad hoc committee, processing 2,000 applicants for military service in less than two months.

These Oxonians, privileged and disproportionately from public school backgrounds, by signing up as soon as possible had longer to get killed compared to other men who took longer or were conscripted in 1916 or beyond. They were in this sense unwitting victims of superior access, premised at the time on the assumption both that the war would be short-lived, and that it was highly desirable to be part of the action.

Drawing out this fact in his single volume history of the University, Laurence Brockliss highlights what might be considered the supreme fact:

The cohort who matriculated in 1913 had the greatest losses, almost 30 per cent being killed, a death rate equivalent to the ravages of the Black Death.

The precise figure was 28.66%.

Now if we turn back to the Corpus vs. Jesus disparity discussed by Winter, we find that 70 per cent of 1913 Corpus matriculants had enlisted by December 1914, versus 35 per cent at Jesus – fully double. This is the principal explanation for the different death rate of each college.

Behind the brute numbers lay other causes. Jesus had its own scientific laboratory, while Corpus was dominated by classicists. It’s not quite true that classicists were useless for non-combatant war work – in at least two cases (Stanley Casson and Sir John Myres) knowledge of Mediterranean geography came in handy at the War Office. But on the whole scientists had a much higher chance of being utilised to a non-combatant war role and Jesus had more scientists than Corpus. It also had more non-commissioned students in uniform reflecting a higher number of non-public school backgrounds, important considering the much higher fatality rate among officers.

Accepting the possible errors of the Roll of Service statistics for the other colleges, Corpus’ fatality rate of 23.82 per cent remains the highest of all the colleges but by a lesser margin than before. Univ suffered 22.73; Oriel 22.34 per cent, All Souls 21.95 per cent, Worcester 20.95 per cent, and Balliol 20.14 per cent.

This does absolutely nothing to dull the recollected sense of devastation of human lives than encircled the High Street, Merton Street and Oriel Square, or what one stayer-behinder described as ‘an unbroken tenor of sad monotony.’

Some of this sense of the college during the war is brought to life wonderfully by Harriet and is an excellent part of the book. But this reviewer also wonders about the students who did stay and what it meant to them.

Contemporary diaries of men who could not enlist are (typically) so cut up with anguish and guilt that there may be scope for dedicated research on the Oxford non-combatants who stayed behind.

The Corpus student population dwindled to just six students for parts of 1917. Who were they, what was their story and how did they cope? T.S. Eliot spent a year at Merton. He was a foreigner being American. Aldous Huxley over at Balliol, was exempted because of bad eyesight. But of the remaining hundred or so students at the University, a rump of approximately 10 per cent after a 1914 undergraduate population of 3,000, there are stories to be told.

One of them is told at length by Harriet, concerning conscientious objection by the brother of the future Prime Minister Thomas Simons Attlee (CCC, 1899). The more celebrated conscientious objector in Oxford was Stephen Hobhouse at Balliol, eventually released from Exeter prison after a sustained campaign by his massively connected family. But Attlee’s case is told in full here by Harriet and is a reminder that to be a so-called ‘absolutist’, i.e. refusing as Attlee did even to perform uniformed non-combatant work, was to go to prison and eat bread and water in solitary confinement. There were about 1300 absolutists nationally and their courage seems remarkable today, a token to freedom of conscience otherwise all but extinguished by patriotism.

In related but slightly different vein is the college President, Thomas Case, who unlike T.B. Strong was no supporter of the conflict. As with Attlee, his unfashionable stance wears well with the passing of time. Case’s motivations were apparently a mixture of regret at losing most of his students, the inevitable and unwelcome fact of sudden change, and perhaps also a deeper feeling that the whole enterprise of the war was, ipso facto, a tragedy in the making because risking the lives of talented scholars. As a classicist he would have been distraught at the break up of a field shared with German scholars. Given what happened, it’s hard to argue that he was anything other than right.

There are many other surprises in the book including meatless guest nights long before veganism became fashionable in the 21st Century; a shortage of coal long before it became implicated in climate change, and even the offer from the War Office of a ‘heavy German gun and carriage’ in 1920, politely declined by Governing Body owing to a lack of space to accommodate it.

While the college appeared to return to ‘normal’ in a matter of months after the armistice, it was superficial. Such a dreadful loss of young life and talent remains substantially without explanation long after the statistics have been agreed.