AN AMMONITE IN AMBER

AN AMMONITE IN AMBER

Why Burmese amber is very exciting to the scientific community

Published: 15 May 2019

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

Jim Kennedy, an Oxford authority on Cretaceous ammonites, Emeritus Professor of Natural History, and former Director of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, has identified an ammonite perfectly preserved in a piece of 100 million-year-old Burmese amber.

The discovery was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on May 13th, 2019.

The concept of amber-preserved insects is hardly new (think Baltic amber, often washed up on beaches there), the amber being dug out of mines in Kachin State in the thickly forested north-east region of Myanmar (Burma), has in recent years wowed the scientific community because it’s much older and has yielded exquisitely preserved and previously unknown terrestrial plants and animals from the age of the dinosaurs.

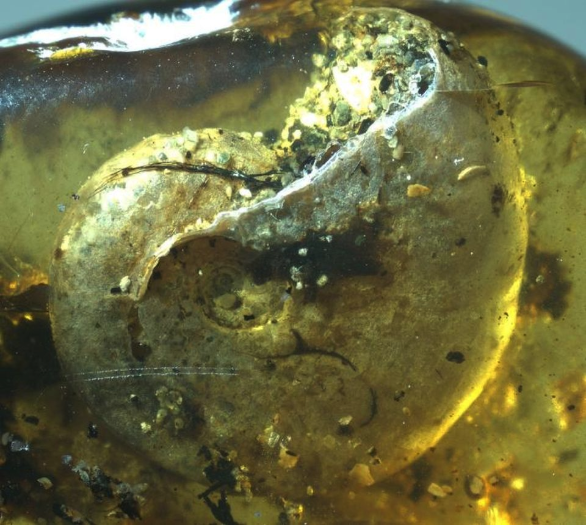

The Burmese amber with the ammonite on the right

Credit: Tingting Yu, Richard Kelly, Lin Mu, Andrew Ross, Jim Kennedy, Pierre Broly, Fangyuan Xia, Haichun Zhang, Bo Wang, and David Dilcher

Burmese amber has been dated using isotopic techniques as 99 million years old. Prized for its clarity, and widely traded with China, it too preserves a remarkable story. From 45 species discovered in Burmese amber by 1999, scientists had by last year identified 1,192 species including spiders, scorpions, snails, worms, flowers, reptiles, birds and even the tail of a dinosaur. Weirdly, given our default assumption that scientists would have nothing to do with Hollywood if they could help it, the plotline of Jurassic Park, the 1993 dinosaur movie, played its own role in stimulating a fascination with creatures preserved in amber. The plot of the film rested on extracting dinosaur DNA from a mosquito trapped in amber.

Ammonite close-up in the discovered piece of Burmese amber

Credit: Tingting Yu, Richard Kelly, Lin Mu, Andrew Ross, Jim Kennedy, Pierre Broly, Fangyuan Xia, Haichun Zhang, Bo Wang, and David Dilcher

The present specimen, at first thought to be a land snail, was subsequently recognised as an ammonite, a representative as an extinct, exclusively marine group of organisms with an external shell. Their closest living relatives are octopus, squid, and Nautilus.

Kennedy’s identification is highly significant because this is among the first marine species ever to be found in Burmese amber. The same fragment also yielded marine snails and a range of other organisms whose living relatives inhabit intertidal and forest floor environments.

But how did these inhabitants, in life, of such different environments come to be trapped and entombed together? There are several possible interpretations. The marine creatures could have been washed into floor of the coastal amber forest by a storm surge, or a Tsunami, or blown in from a beach. Alternatively, the still sticky resin could have fallen or been washed onto a beach from coastal trees and picked up the corpses of dead marine animals; the jury is still out on this.

Jim Kennedy, Emeritus Professor of Natural History, University of Oxford

Kennedy notes, ‘I was sent photographs via Andrew Ross in Edinburgh and knowing a bit about Cretaceous ammonites was able to describe, identify, and interpret it. The project was a truly international one, with co-authors from China, the U.K., France and the U.S.A; that’s how science works these days.’

‘Kennedy has over 450 academic papers to his name, mainly concerning the Cretaceous period, its rocks, fossils and environments, and has worked in Europe, Asia, The United Stated, North and South Africa. Awards include the Gold Medal for Zoology of the Linnean Society.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) first published May 13, 2019