HEAVEN’S GATE: DIARY OF AN EXTRA

HEAVEN’S GATE: DIARY OF AN EXTRA

Colin Ridler recounts how his father took part in the Oxford making of the movie Heaven’s Gate, now the subject of a book

Published: 14 March 2023

Author: Colin Ridler

Share this article

My father Vivian Ridler (1913-2009) was Printer to the University 1958-78, an office that dated back to the start of Oxford University Press in the sixteenth century, but ended when that part of the business, situated in Walton Street, was closed in 1989. The role involved production of books, rather than their acquisition and editing, and has been told in his posthumous book Diary of a Master Printer (2022).

But this memoir concerns his role as an extra in a Hollywood film that was shot in Oxford in 1980.

Vivian had recently retired. He read that Hollywood was coming to town and required extras, he eagerly signed up, keen to witness how a professional movie was made.

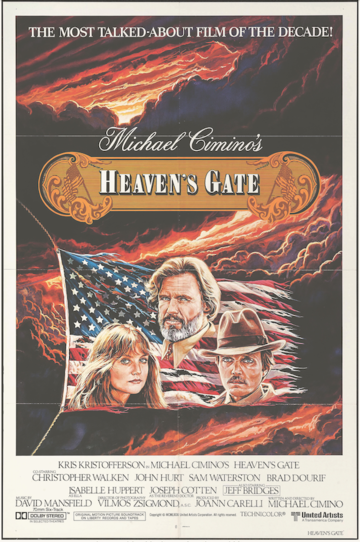

The movie was a Western called Heaven’s Gate, and during the week-long shoot in April 1980 Vivian kept a detailed daily diary, drafted in his beautiful italic script and later pasted into a blank book that also included photos, movie call sheets, his plans showing where the film cameras were positioned, as well as newspaper cuttings. Much of this material (together with the complete diary, typeset) is reproduced in the new book, Heaven’s Gate: The Diary of an Extra. It also includes a further section listing the full cast (notably Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, Isabelle Huppert, John Hurt and Jeff Bridges), and describing the entire plot, a month-by-month account from initial script to premiere, the experiences of its stars, the changing critical reaction over three decades, and discussion of all six of the director’s other movies.

Who, then, was the director? And why was he filming a Western in Oxford?

Michael Cimino got his break as a rookie director working for Clint Eastwood on a heist movie he also scripted called Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, starring the Spaghetti-Western star and Jeff Bridges.

Shot in a tight 49 days and quite well received on its appearance in 1974, it nevertheless opened no doors for Cimino since it was seen as an Eastwood film.

By contrast his next movie, The Deer Hunter, achieved fame and acclaim as the first successful – if controversial – film about the Vietnam war, winning five Oscars at the 1978 Academy Awards. Shot extravagantly across eight US states and in Thailand, using 100 hours of film and costing double the contracted budget, it gave a foretaste of what was to come with Heaven’s Gate, which started filming as the Oscar awards for The Deer Hunter were announced.

As far back as 1971 Cimino had drafted a script for The Johnson County War, about a little-known episode in Wyoming during the 1890s when established cattle barons attacked the poor immigrant homesteaders of Johnson County for rustling the ranchers’ steer (a theme also intrinsic to the classic Western Shane (1953)).

Now, flush with his Oscars success, Cimino felt no inhibitions about fulfilling his vision for what had been retitled Heaven’s Gate (to make it sound less like an unfashionable Western).

A contracted 69-day schedule in 1979 became six months for the main part of the film shot in Montana, the budget ballooned to more than three times the agreed $11.5 million, and the result was 220 hours of film that would take a year to edit and cut. The hapless film studio, United Artists, finally wrested control of the production from Cimino, insisting that if he wanted to have his as yet unmade Prologue to the film, its budget must be cut from the projected $5.2 million to $3 million.

By this time Cimino had settled on Oxford as the location for the Prologue. He wanted the main lead, Kristofferson, to be shown as an idealistic young man graduating from Harvard University in 1870, accompanied by his more cynical friend played by John Hurt.

Harvard had declined to participate, but Oxford (used as a location for films such as Joseph Losey’s Accident (1967)) was happy to accept the money. We thus have the anomalous opening shot of Kristofferson running beneath Tom Tower, then miraculously straight along Queen’s Lane, New College Lane and Catte Street, where he catches up with Hurt and their fellow students as they process behind a band playing When the Saints Go Marching In, finishing up in the Sheldonian for the graduation ceremony.

Here Hurt, as Class of ’70 orator, makes a facetious speech, while Kristofferson periodically casts an admiring eye towards a glamorous young woman in the gallery (who will reappear mysteriously much later in photographs glimpsed out in the American West, and in the closing Epilogue aboard a steam yacht with Kristofferson in 1903).

Vivian, playing a Harvard elder, complete with top hat and austere dark coat, (shown right) took such a keen interest in observing these scenes that Cimino spotted him in Queen’s Lane while filming Kristofferson sprint up the lane.

Calling for Vivian to stand in front of a carriage, as the diarist records, “He asked me to turn my head, watching Kristofferson as he ran past. ‘No expression, unless you want to look angry at what we’re doing to your road.’ He also ordered the props man to fit me with John Hurt’s steel glasses. Props then said he also had a pair of gold-rimmed ones . . . but when he put them on me he said ‘I think they look bloody awful.’ I suggested we go over and show Cimino. He took one look and said ‘very good’. Collapse of props.”

With his reduced budget for the Prologue Cimino had to shoot the Sheldonian sequence (shown below left) in just one day, which thanks to his endless takes and retakes required filming into the evening. As a result the student extras went on strike for overtime pay – and won. During another pause in filming Vivian encountered John Hurt in The White Hart pub, who told him the high cost of hiring the Sheldonian. Filming then moved to Mansfield College (standing in for Harvard green), where Vivian had previously witnessed a giant crane lift a huge beech tree (denuded of branches, later bolted back on) into the centre of the quad (shown, top). Round this tree the new graduates now danced a celebratory waltz to the strains of the ‘Blue Danube’, watched by their elders including Vivian (deafened by the music blaring from the loudspeakers). In the new book the scene is powerfully captured by a two-page overhead colour photo, accompanied by Vivian’s informative plan showing camera positions.

At last, one year late, Heaven’s Gate was released in November 1980. But American critics slated it – partly because the secretive director had shunned the press – and at the US box office it took only $3.5 million to set against the full $44 million production cost. A new sense of patriotism under Ronald Reagan also meant that the final showdown in the film, where the US cavalry rescues the villainous cattle barons, was hardly a crowd-pleaser.

The movie achieved notoriety as the catalyst both for the subsequent sale of a historic studio, United Artists, to MGM, and for supposedly bringing to an end the decade-long era of directorial autonomy. Cimino’s contemporaries such as Coppola and Scorsese blamed him, fairly or unfairly, for wrecking their own careers. He never made a significant movie again, and died in 2016.

Ironically the theme of injustice and prejudice, of immigrants versus the wealthy elite, has found a new resonance in the 2000s, meaning that many now rate the improved 2012 ‘director’s cut’ version of Heaven’s Gate a masterpiece.

PICTURE CREDITS:

TOP, PICTURE of DANCE: Photo 12/Alamy Stock Photo; SECOND PICTURE of FILM POSTER, COPYRIGHT United Artists; THIRD PICTURE of Vivian Ridler in Top Hat, Colin Ridler (also used as listing image); FOURTH PICTURE inside SHELDONIAN, Courtesy of the BFI National Archives.

Heaven’s Gate: The Diary of an Extra by Vivian Ridler. Edited by Colin Ridler. Foreword by Nicolas Kent of Oxford Films. The Perpetua Press, Oxford.

Vivian Ridler (1913–2009) gained international renown as one of the last Printers to the University at Oxford, an office stretching back to the very founding of Oxford University Press in the sixteenth century. As readers of his Diary of a Master Printer – published last year by Perpetua Press – will know, however, his accomplishments extended well beyond the art of fine printing. In particular, he was an avid film buff and skilled 8mm filmmaker, shooting innumerable comedies, adventure stories and documentaries that culminated in his masterpiece, 1851, where using a storyboard and a script derived from Queen Victoria’s diary of attending the Great Exhibition, he filmed many of the vivid colour lithographs of this seminal event, now in the Bodleian Library. He was a Fellow of St Edmund Hall 1965-2009.