OXFORD DOCTORATE A BEST-SELLER EIGHT DECADES AFTER PUBLICATION

OXFORD DOCTORATE A BEST-SELLER EIGHT DECADES AFTER PUBLICATION

Capitalism and Slavery by Eric Williams hits the best seller list in 2022; a lesson in history

Published: 9 March 2022

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

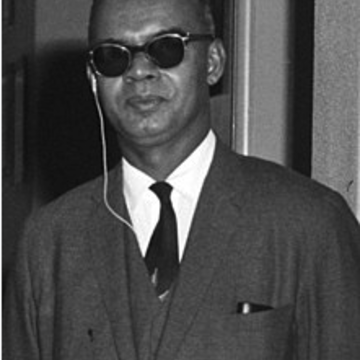

The author Eric Williams (St Catherine’s, 1932), who went on as Prime Minister to lead his native Trinidad and Tobago to independence from Britain in 1962, had enormous difficulty publishing his Oxford doctorate of 1938, finally succeeding only in 1944 in the US, and later in 1964 in the UK.

Capitalism and Slavery has just been published as a Penguin Classic in February 2022, with immediate success.

Racism featured in the difficulties Williams faced in 1938, but it wasn’t as potent an aggravation to his detractors as Eric’s actual arguments, which kicked over the received narrative of how slavery was ended by Britain, and above all why it was ended.

This publication in 2022 by Penguin not only shows how hopelessly behind the UK has been in discussing and accepting slavery as part of Britain’s troubled imperial past, but how hard it has been to accept the essential nature of that slavery in the first place, as an expression of economics and capitalism.

Williams’ doctorate was brilliant and like so many brilliant theses it was wide ranging and thus open to dispute.

Britain had fallen into a stupendously lazy and mostly erroneous habit, he argued, of celebrating the emancipation of the slaves as a moral and religious achievement of William Wilberforce (1759-1833) and others around him, known as ‘the saints.’

Williams argued that the true reason for the end of slavery wasn’t moral and religious virtue so much as self-interest expressed as free trade, at a moment in the 19th century when Britain was ascendant in all matters and ruled the waves.

West Indian plantation owners had succeeded under protective, mercantilist conditions that belonged to the 18th century, among them certain navigation laws and preferential duties to protect British trade from competitors.

The big idea of the 19th century was free trade, and it pointed away from such protectionism.

The ironic result of ending slavery in its own plantations was that the cost of sugar in Britain fell as cheaper supplies became available on the ‘free market’ – which by the 1840s meant slave sugar but from Cuban and Brazilian plantations instead.

None of the sanctimonious saints had much to say about that glaring contradiction, argued Williams, and nor did they have any apparent problem with the slave cotton that poured into Liverpool and Manchester from the American South.

Viewed purely in economic terms, Britain had climbed the ‘value added’ ladder and could now become rich from manufacturing and exporting, leaving the production of raw commodities to other, ‘non-British’ slaves while celebrating its own distancing from the dreadful practice.

Perhaps the key quote in the whole book, which is offered as economic history rather than as a study of slavery itself, is on page 128:

‘The attack on the West Indians was more than an attack on slavery. It was an attack on monopoly. Their opponents were not only the humanitarians but the capitalists.’

Williams stated that the three key events were the abolition of the Slave Trade in 1807, the ending of slavery in 1833 and the ending of the ‘sugar preference’ in 1846.

‘The three events are inseparable.’

Of course, the subject is staggeringly complex and a ready number of scholars tried to demolish Williams’ argument in the years after its publication, particularly with reference to how well British plantations did during the American Revolution and Napoleonic wars.

There was to some extent a degree of economic self-harm as Britain ended its own slave practice; it could not be otherwise.

Similarly there was idealism and moral energy behind the abolitionist position; a point also accepted by Williams.

But his larger point is that the abolitionist idealism was mired in other ironies and avoidances, and that slavery, and its demise, was in essence about capitalism more than it was about anything else, even though 'anything else' amounted to something.

Williams' book was, and remains, a turning point in the historiography of empire even while other more comprehensive narratives have been published, such as David Olusuga’s acclaimed Black and British, A Forgotten History.

There’s a wonderfully luminous note offered by Williams towards the end of his review of his sources (the hallmark of a doctorate turned into a book, and none the worse for it -) where he cites Marguerite Steen’s best-selling 1941 novel The Sun is My Undoing.

This novel, largely forgotten now, was 1,200 pages long and the hero is a slave trader. It sold out on both sides of the Atlantic and involved horrific detail about the ‘true’ condition of slaves. It was also predicated on the economic imperative of owning slaves.

The book aroused no criticism of the truth of its essential narrative, which concerned ‘the triangular trade and its importance to British capitalism,’ noted Williams.

In a rather discerning way, he had pointed out that no one objected to ‘slavery as capitalism’ when it was explored in a swashbuckling historical novel.

In fact, it was tantamount to stating the obvious.

But re-stated as historical truth, it was an incendiary bomb that almost no one could countenance, including the first UK publisher that Williams approached, Fredric Warburg, a leading publisher of revolutionary texts who had put out all of Stalin’s and Trotsky’s works.

Warburg turned down Williams, bluntly stating, ‘I would never publish such a book, for it would be contrary to the British tradition.’

That view might now be ending, but only after eight decades of relative silence and historiographical complacency.

Williams’ daughter, Erica Williams Connell, is the founding curator of the Eric Williams Memorial Collection Research Library, Archives and Museum at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago.

Noting that the book has already reached the best seller lists in the UK, selling over 3,000 copies within days of being published by Penguin, she told the Guardian newspaper,

‘Everyone who has heard about the book finally being re-published in the UK has said the same thing to me: well, it’s about time!’

Picture credits

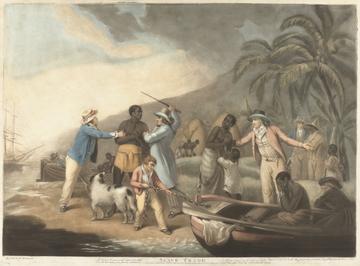

Lead image, Shutterstock (caption: British abolitionist broadside (poster) demonstrates the crowding of a standard slave ship the BROOKS built in 1781, Ca. 1790 engraving with modern colour)

Slavery print, Shutterstock; portrait of Eric Williams Wikicommons

Book jacket of Slavery and Capitalism by Penguin Random House

Book jacket of The Sun is My Undoing Wikicommons