HAIL THE DESIGNER ELECTROLYTE

HAIL THE DESIGNER ELECTROLYTE

New materials conduct ions in solids as easily as in liquids, a hugely promising discovery

Published: 6 January 2026

Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

Normally, when liquids solidify, their molecules become locked in place, making it much harder for ions to move and leading to a steep decrease in ionic conductivity.

Now, however, scientists have synthesised a new class of materials, called state-independent electrolytes (SIEs), that break that rule.

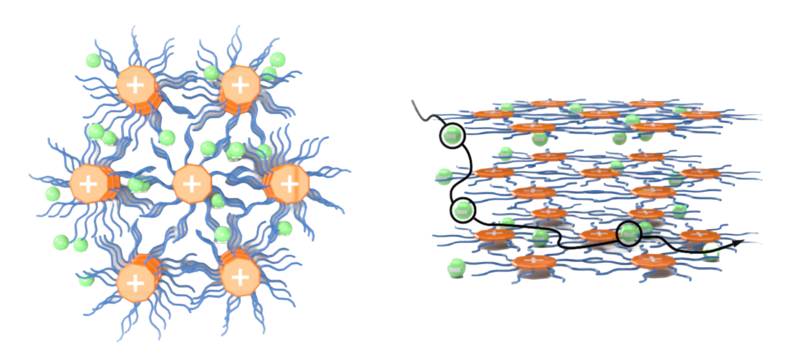

The team achieved this result by designing a new class of organic molecular ions with special physical and electronic properties. Each molecule has a flat, disc-shaped centre surrounded by long flexible sidechains – like a wheel with soft bristles. Positive charge is spread out evenly across the molecule by the movement of electrons, which prevents it from tightly binding with its negatively charged partner. This allows the negative ions to move freely, flowing through the side-chains (the ‘soft bristles’).

Then, in the solid state, these organic ions naturally stack on top of each other, forming long rigid columns surrounded by many flexible arms: much like static rollers in a car wash. Despite forming an ordered structure, the flexible side chains still create enough space for the negative ions to continue moving as freely as they would in a liquid.

The result: a dynamic ordered structure that allows the negatively charged ions to move through just as easily in the solid state as in the liquid form, with no sharp decrease in ionic conductivity.

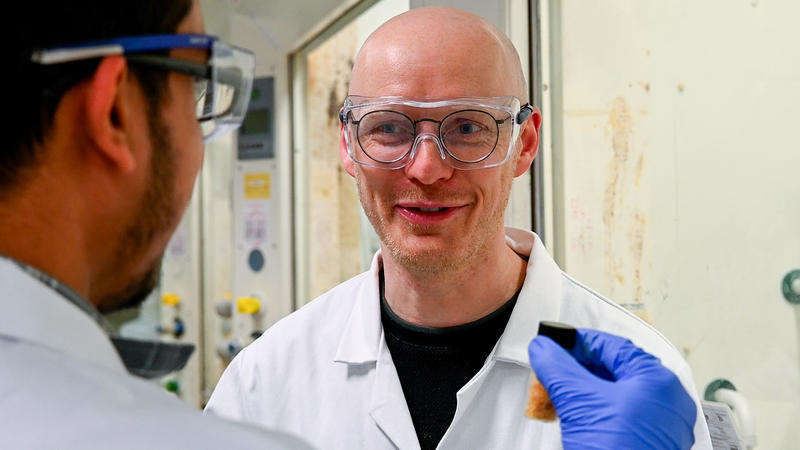

Lead author Paul McGonigal, Professor of Organic Chemistry at Oxford and a Fellow of Merton College, says: ‘We designed our materials hoping that ions would move through the flexible, self-assembled network in an interesting way. When we tested them, we were amazed to find that the behaviour is unchanged across liquid, liquid-crystal, and solid phases. It was a really spectacular result – and we were happy to find it can be repeated with a few different types of ions.’

QUAD caught up with Professor Paul McGonigal to get a feel for the range of commercial applications and possible scalability of the discovery.

The main application for the foreseeable future will be micro-electronics and computing, where you could imagine depositing a liquid electrolyte so that it confirms exactly to a surface, only then solidifying.

We asked if the discovery has application in electric cars, but Professor Paul McGonigal says that so far it is ‘the negatively charged part that moves around quite freely. But what would be really nice is to switch that around so that the positively charged part can move around so that we could have conductivity of something like lithium or sodium which is really useful for battery technologies.’

For now the experiments are being conducted at the gram level rather than the kilogram level, indicating the need for further research to attain the sort of scale that might find its way into a car, where the hunt for lighter, more energy-dense battery cells is akin to the hunt for the Holy Grail.

Professor Paul McGonigal recently came to Oxford from the University of York, bringing some of his team with him. He says that now the design criteria are understood, ‘we can use organic synthesis to quite easily change these structures and optimise them from here.’

Dr Alyssa-Jennifer Avestro, Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellow at Oxford, discussed the findings with Professor Paul McGonigal in a short video that brings the subject to life.

She says, ‘I think that’s the most exciting aspect of the research, that these are being all developed through organic synthesis. So, relatively straightforward methods but with a very vast toolbox of chemistry.’

PhD student at the University of York, Juliet Barclay, first author on the study and from 2026 a postdoc at Manchester University, says: ‘As a PhD student, it’s incredibly rewarding to discover something that changes how we think materials can work. We’ve shown that organic materials can be engineered so that the movement of ions doesn’t "freeze out" when the material solidifies. This opens new possibilities for safer, lightweight solid-state devices that work efficiently over wide temperature ranges.’

This work is a collaboration between scientists at the Universities of Oxford, York, Leeds and Durham, with partners in Portugal, Germany and the Czech Republic.

The discovery could lead to new classes of flexible and safe solid electrolytes, in that sense ushering in the era of the designer electrolyte.

One potential use case could be adding the electrolyte into a device as a liquid at a slightly elevated temperature, allowing it to make a good contact with the electrodes, before cooling to ambient temperature and using it in a safe solid form without losing ionic conductivity.

The resulting solid electrolytes have potential applications in batteries, sensors and electrochromic devices, where organic solids are generally advantageous over inorganic materials because of their lightweight and flexible physical properties, and the potential to source them renewably.

One day the same or similar approaches may make their way into larger devices extending to personal mobility, but Professor Paul McGonigal says, ‘I always worry about overclaiming, so we should be cautious. However, the decision to publicise the findings in Science is relevant here, and I believe we are talking about a fundamental advance. The phenomenon hadn’t been observed before.’

The research team at Oxford are now working to increase the conductivity and versatility of the materials, as well as using them in electronic devices for computing.

IMAGES:

Lead image: Dr Paresh Behera (left) and Professor Paul McGonigal (right). Credit Thomas Player

Illustrative image: Schematic illustration of the SIE solid-state superstructure and properties. The mobile ions

(green) diffuse through a network of columns of the organic counterions (orange). Credit: Professor Paul McGonigal.